The Next Generation of Innovators in Agriculture

“There is no known abatement of fragipan,” said Dr. Phillips Phillips, a researcher with the USDA’s Agriculture Research Service (ARS) in Ames, Iowa. “Until now, that is,” she added. “Annual ryegrass is a good one, because the chemicals in ryegrass roots break down fragipan.”

Phillips and the congressionally-funded ARS are delving deeper into the mystery of why annual ryegrass has this effect on fragipan. She said there are 50 million acres of agricultural crop land impacted by fragipan in the U.S. alone. “And fragipans are a problem around the globe,” she added.

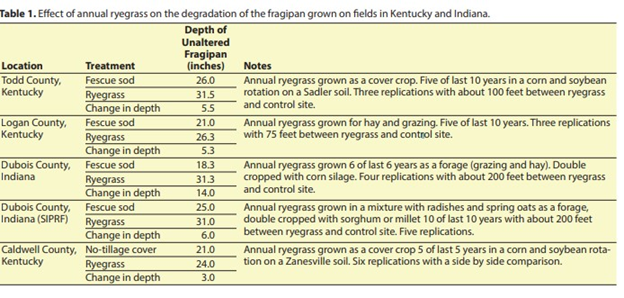

Phillips and colleagues have proposed work to follow that of Lloyd Murdock, who for the past decade has been documenting and testing the effect of annual ryegrass on fragipan in laboratory settings and in the field. Murdock’s research at the University of Kentucky found that a chemical exudate from ryegrass roots is the reason. Specifically, the chemical excretion from annual ryegrass roots systematically changes the chemistry and make-up of that compacted soil, effectively reducing the presence of fragipan. In the following graph, taken from Murdock’s study, you can see how annual ryegrass reduced the depth of fragipan and increased the depth of healthy soil in five locations in two Midwestern states.

Phillips is leading a five-year study on annual ryegrass’ effects and how to augment them. “A key part of our research will quantify how annual ryegrass, used as a cover crop, affects the amount and availability of water in the field,” she said. “By reducing fragipan, we may be improving drainage and thus expanding the window for planting in the springtime,” Phillips added. “And we think that reducing fragipan will make more soil water available during the summer too, by increasing root depth. We want to measure how much more available soil water is present, and whether the crop can put on more leaf area and experience less water stress.”

John Pike, a former University of Illinois ag research manager, will be monitoring the study in Illinois, funded by the Oregon Ryegrass Seed Growers Commission.

“Mike Plumer and other pioneers showed that annual ryegrass can be really useful in Southern Illinois, Missouri, and Kentucky,” Phillips said. “As our weather continues to change, ryegrass could increasingly be seen as a ‘climate adaption tool.’ Specifically,” she explained, “in the Midwest we’re having more rain in the spring, and the rain events are bigger. I hope annual ryegrass’ ability to reduce fragipan will allow more water to be absorbed into the field instead of running off. So, even with more rain, farmers will be able to get into the field in a timely fashion, simply because the water will infiltrate more quickly rather than pooling or creating erosion.”

“Additionally,” Phillips continued, “the month of July in the Midwest is becoming hotter and dryer than in the past. July is when the corn most needs moisture. Annual ryegrass, by helping to create deeper soils may be able to make up for that reduced precipitation.”

Phillips’s colleague, Dr. Dan Olk, will lead complementary studies on how annual ryegrass chemically degrades fragipan. Olk, a biochemist, is an expert on humic products, which are derived from young coal deposits and are thought to enhance plant growth. Hypothetically, humic products used in conjunction with annual ryegrass may have a compounding effect on the decay of fragipan and enhancement of crop health. Phillips and Olk will look at samples of fragipan soil collected from Kentucky and Illinois in different stages of degradation. “We want to find out how the chemistry of fragipan changes at different stages of breaking down, and whether humic products change the rate of fragipan disintegration,” Phillips said.

While Phillips is focused on the science and field work, John Pike will also be sharing the educational aspects of the work with a variety of audience, from field day demonstrations to trade shows. Phillips acknowledged the importance of a team approach to this and other projects. “I’m very thankful to those who are partnering with us in our efforts, like John Pike, the Oregon Ryegrass Commission, and Oregon seed growers, who continue their on the ground support for this work.” She also acknowledged Ryan Hayes, an ARS colleague who works on plant breeding at Oregon State University, where she worked before moving to Iowa in 2020.

Some worry about how the adoption of cover cropping and regenerative agriculture will keep expanding, as a generation of cover crop pioneers like Mike Plumer and Lloyd Murdock retire. It is refreshing to see the next generation of growers and scientists, like Phillips, stepping in to develop the place-specific knowledge necessary to make cover cropping work in a challenging environment where it can have the most benefit.