Meet Mark Mellbye – Oregon’s ‘Johnny Appleseed’ of Annual Ryegrass – Part 1

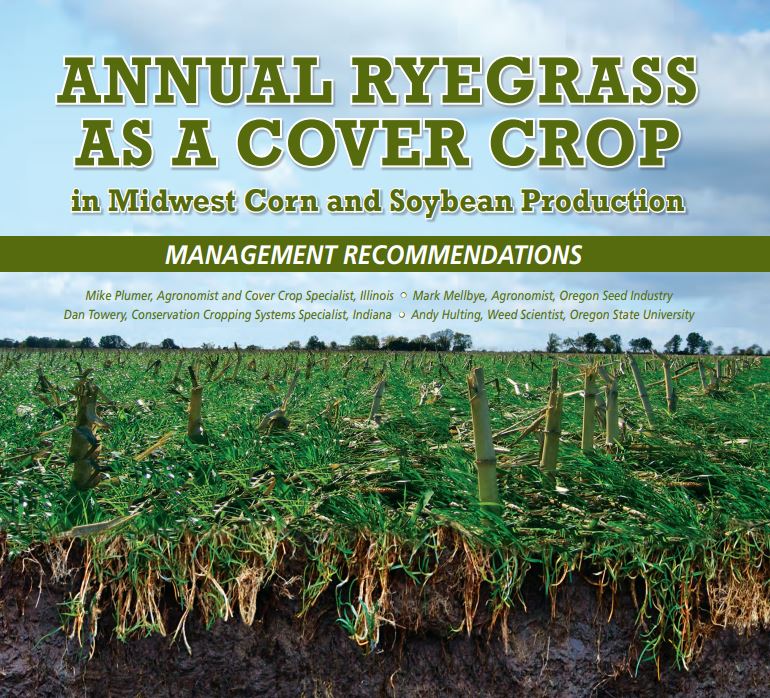

As you may have read, Oregon grass seed growers and the state’s Ryegrass Commission were largely responsible for giving the Midwest cover crop initiative a substantial push over the past 25 years, as has been summarized in previous posts.

The growers you’ve read about in this series, namely Don Wirth and Nick Bowers, both named another Oregonian for acknowledgement, who put a considerable imprint on the project’s success. That man is Mark Mellbye.

Mellbye was raised in Oregon and earned two ag-related degrees from the state’s land grant college in Corvallis – Oregon State University (yes, another OSU!). He joined the Peace Corps after his first graduation and spent 18 months in Lesotho, teaching science and math, then another year traveling throughout Africa.

Before taking a position back at his alma mater, in 1986, Mark was an extension agent in Washington State. The nature of his position at OSU, he said, matched the state’s interest in helping to promote Oregon ag products, and that’s why he was able to spend so much time with Midwest cover crops in the past 25 years.

“A large part of my work in Oregon was to respond to local growers’ requests,” Mark said, “to work on projects of use to them.” Before he retired, Mark was the District Agronomist, overseeing OSU Extension projects in three counties, collectively known as “the grass seed capital of he world”. “The other aspect of my job, and the University was very supportive of this, was to help extend the marketplace for Oregon seed. The Midwest cover crop initiative was the focus.”

He added, “Of course, I was only marginally responsible for what happened with annual ryegrass adoption in the Midwest, but it’s impressive to think that when we started in the late ‘90s, there was no annual ryegrass seed sales to the Midwest whatsoever. Today, there’s upwards of 20 million pounds being shipped there for cover crop use annually, out of about 200 million pounds of annual ryegrass seed produced in Oregon.”

Mike Plumer’s name is forever linked with pioneering cover crops in the Midwest. What is less known is that Plumer, the Illinois crop advisor, didn’t consider annual ryegrass as a possible cover crop until he met Mark in 1997 and they began working together. Until then, Mike had been dabbling with cereal rye, winter wheat, hairy vetch and peas as cover crop potentials. And, as those who knew Mike understood, he was very principled and would immediately balk if he sensed he was being used for some commercial purpose, including the sales of annual ryegrass.

For the cover crop project to succeed, it would have to succeed on a number of fronts. After all, change is hard for most people, and new things tend to have bugs to work out before they are widely accepted.

“One hurdle was that the equipment needed to plant any seed into a no-till field – whether you’re talking corn, soybean or cover crop seeds – was in the process of significant upgrade and modification,” Mark said. “Today, machines can consistently plant those seeds into residue and even into green standing cover crops. Another hurdle was that the nature of annual ryegrass growth in cash crops was an unknown, but the notion was already out there that it should not be trusted. There was a suspicion, generated mostly by weed scientists, that annual ryegrass would become uncontrollable if it got loose in Midwest cornfields.”

“We’ve largely cleared those hurdles,” Mark said, “and we’re on our way to clearing the next one, which is largely educational. It may take the next generation of growers to accept the idea that conventional tillage is too expensive, and that despite the learning curve, cover crops are better for the wallet, for the soil and for the environment.”