Dan Olk went to the Philippines after earning his PhD at UC Davis, accepting a post-doctoral position with Dr. Ken Cassman at the International Rice Research Institute. They were investigating a global problem with declining rice productivity. “The plants were making use of fertilizer nitrogen but not soil nitrogen, despite the abundance of nitrogen in the soil,” he said. After years of study, they developed a winning strategy. By changing the seasonal management of rice crops and aerating the soil when the crop residues were decomposing, the trapped nitrogen could be released from organic matter. A few years later, a comparable project in Arkansas rice confirmed these results.

After joining the USDA in Iowa in 2001, Dr. Olk’s sleuthing continued to reveal why nutrients get bound up in soil chemistry, for rice growers internationally as well as domestic corn and soybean producers. Beyond his efforts to unleash the potential of organic matter, Olk has also spent many years investigating the use of “humic products” (made from young coal deposits) and their ability to stimulate plant growth.

The annual ryegrass cover crop project in the Midwest had been rolling along for more than 15 years when it came to Olk’s attention through the work of Dr. Lloyd Murdock, who had been researching the effect of annual ryegrass cover crops on fragipan soils located in Kentucky and Indiana. Olk and his USDA colleague, Dana Dinnes, were presenting a seminar on humic products at the 2016 National No-Till conference. Murdock was receiving an award at the same conference, and that’s when the men met. Murdock was being honored for his decades of research on no till, which shows tremendous potential for boosting agricultural productivity and soil health.

Because fragipan, a nearly impermeable layer of compacted soil, is so pervasive in the US (50 million acres), the USDA has become interested in putting some of its considerable heft behind this new discovery. Dr. Olk will lead a new research project that will pick up where Murdock’s work at the University of Kentucky left off.

If you’re new to the story, here’s a quick summary: Junior Upton, working on his southern Illinois farm for decades, discovered in the 1990s that annual ryegrass added value to marginal land under which fragipan lay. Before trying annual ryegrass as a cover crop, Junior noticed that corn roots would grow down only to the edge of the fragipan layer (18 – 24 “deep) and then deflect sideways, unable to penetrate.

But when corn in the fields covered by annual ryegrass began to outproduce neighboring fields, especially in drier years, he asked agronomist Mike Plumer to help him understand why. Plumer, then at the University of Illinois Extension, came out with digging and soil coring equipment. In four-foot soil pits, they discovered annual ryegrass had exceedingly long roots that grow throughout the winter, even with scarce top growth. That was their first “aha!” The second one, which now has the USDA’s interest, is that ryegrass roots pierced the compacted soil and, thus, gave corn plants more rooting depth, additional nutrients, and moisture. With that encouragement, Junior planted annual ryegrass on his entire farm, year after year, and his soil health continued to improve as row crop yields increased. When he first planted annual ryegrass and began collecting data on corn production, his corn yield was 15 bushels per acre (bu/ac) below the county average. In 2020, after 20 years of continuous no-till and annual ryegrass, the same field produced 30 bu/ac more than the county average.

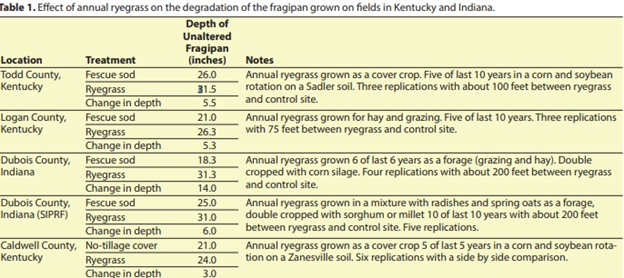

Murdock heard about Junior’s and Plumer’s discovery and spent more than five years documenting what they were seeing in Junior’s fields, as well as replicating field trials in four other farms in three states. Murdock and his university team also took the experiments into greenhouses and their laboratory to find out more about the chemistry and mechanics – trying to understand why annual ryegrass seemed to degrade fragipan, where nothing practical and sustainable was found to do that in the last half century of research. His lab partner, Dr. Tasios Karathanasis, submersed chunks of fragipan in several different solutions, one of which was a ryegrass extract.

“Within two to four weeks we began to see the ryegrass extract break down the fragipan,” Karathanasis said. They found that annual ryegrass extracts were unique among all test solutions, the only one to affect the integrity of fragipan. It led Murdock and his team to suggest that annual ryegrass roots exude chemicals that loosen the molecular bond in fragipan soil, which ryegrass roots then penetrate and pry away.

And when Murdock added a humic product to his greenhouse tests, the annual ryegrass appeared to have had an even greater impact on fragipan degradation.

Although Olk had met Murdock at the No Till conference in 2016, he had not become much more familiar with the cover crop project, nor the people Murdock worked with, including Junior Upton, Mike Plumer and John Pike, a research agronomist with the University of Illinois. Then in 2021, the USDA lab where Olk works hired Dr. Claire Phillips, who had academic roots in Oregon and who knew about the cover crop work being done on Junior’s farm. In fact, she had met Mike Plumer on his Oregon trips, where he reported on the cover crop project, including Murdock’s research. Phillips made the introductions and the deeper connection to the USDA research team began.

Olk’s research will delve ever deeper into the mystery. In the 5-year project plan written to support the research, Olk said: “Two proposed mechanisms (to demonstrate how fragipan is weakened through annual ryegrass cropping) are that (1) ryegrass growth creates a solution with a high sodium saturation ratio, which disperses fragipan particles; and (2) ryegrass root exudates contain chelating agents, which bind to aluminum and iron molecules in the fragipan, thus helping to disintegrate those cementing agents within the fragipan.”

Another characteristic of fragipan is that it causes overly wet surface conditions early in the growing season, due to poor natural drainage. Later in the season, crops dry up because the shallow water supply evaporates or is absorbed quickly by the crop.

The USDA research will address that issue as well, relying on further field work in a number of Midwest locations, including Junior’s farm in Illinois. Additional lab and greenhouse research will continue in Kentucky, as well as at the USDA labs in Iowa.

Here are more specifics as to the scope of Olk’s research, related specifically to annual ryegrass:

- “We will look more closely at the impacts of long-term artificial drainage on soil health.”

- “We will study

the seasonal soil hydrology of corn-soybean rotations with and without annual

ryegrass winter cover crops. We will test the hypotheses that (1) ryegrass

growth removes excess soil moisture in springtime, and (2)

- “We will determine the chemical composition of fragipans at varying stages of degradation by annual ryegrass and humic product application”

- “We will determine the effects of a humic product on root exudates released by annual ryegrass in a hydroponic (lab) system.”

After his research, Murdock said the use of annual ryegrass, as a cover crop, could dramatically change the output of crops on fragipan soils internationally. Olk’s research will evaluate that claim. If proven true, annual ryegrass could become an inexpensive method to add profit to formerly marginal acreage. It would also help to lift a burden that has restricted agriculture on fragipan soils for centuries.