The Chemical in Ryegrass that Crumbles Fragipan

The hunch that annual ryegrass use was breaking down the fragipan at Junior Upton’s farm in Illinois was like music to Lloyd Murdock’s ears. The University of Kentucky (UK) research team had begun to experiment with different chemicals in the greenhouse and field where he worked at the University of Kentucky’s Princeton farm and in the lab on the main campus.

While they waited for results on field plots of annual ryegrass they planted that year, the UK research team began working with the plant in controlled lab and greenhouse environments. They created extracts made from annual ryegrass roots, as well as from the foliage. “Naturally cemented fragipan clods were placed in a solution of annual ryegrass extract. Thirty days later the size and distribution of the remaining aggregates were determined. As the binding agent in the fragipan is dissolved by the chemical, the fragipan clod begins to fall apart. The greater the dissolution of the binding agent, the smaller the remaining aggregates. Ag related chemicals were also tested but it was annual ryegrass that demonstrated the most significant ability to dissolve the cementing agents biding the fragipan particles,” he said.

Lloyd also made numerous trips to visit Junior’s farm in those years, to authenticate what they were experiencing there, and to apply what was being gleaned. “We’ve known, for example, that some plants do not exert much pressure at the root tip. Annual ryegrass roots tips, on the other hand, exert a high amount of pressure,” Lloyd said. “So those roots will seek out a crack or weak spot in the fragipan and break through there. It doesn’t take many roots getting through to make a difference. And when corn roots follow those same channels the following year, they’re getting access to nutrition and moisture below the fragipan,” he added. The combination of plant chemistry and root pressure has a dramatic effect on fragipan.

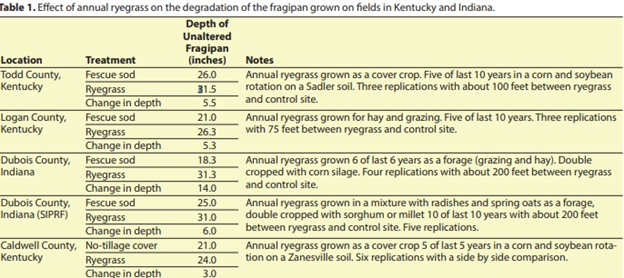

The UK team did replicated trials in five Kentucky and Indiana sites. Below, Table 1 shows, in controlled studies, annual ryegrass reduced the thickness of fragipan significantly at each site, allowing more soil depth for crops.

Dave Fischer is a beef producer from Indiana, and it is his Debois County farm mentioned in the table above. Fisher has planted annual ryegrass on his farm for the past eight years. “When I visited his farm last year, I found that he had lowered the fragipan depth by 14 inches and had annual ryegrass roots 29 inches deep,” Lloyd said.

“Those results floored me,” said Fisher in a video on the project. “But at the same time, I had noticed that these fields seemed to not dry out as fast compared to what they used to and to neighboring fields. We were hanging in there a lot longer during drought periods,” he said. “I would plant it just because of the forage, but the addition of breaking up the fragipan has just been super.”

“I’m more excited about this research than any other project I’ve worked on in my 45 years at the University of Kentucky,” Lloyd said in a University news article, “because it can help so many people. It is something that farmers can work into their operations now to increase their yields.”

As he prepared to retire once again, Lloyd said he has been grateful for the Oregon Commission, and others, whose support was crucial for the UK team’s work on annual ryegrass research. “And it looks like others who have noticed our work are picking up where we’ve left off,” he said with a smile. “Claire Phillips, who received her PhD from Oregon State University and has been a soil scientist for the USDA in Iowa for six years, as well as Dr. Dan Olk and Dr. Dana Dinnes are interested in continuing the work we began. And, likewise, John Pike, an agronomist at Southern Illinois University, has also expressed interest in helping to further the research of fragipan and to continue promoting the use of annual ryegrass as a cover crop.”